The Remarkable McLaughlin Sisters: Lilian, Josephine, and Madeline

While conducting research on the life of Marjorie O’Connell (Shearon), I had the opportunity to transcribe a series of letters she wrote to palǣontologist Barnum Brown in 1920, while he was off searching for oil and fossils in Abyssinia. That led me to looking into his life story, which led me to his second wife, Lilian, which led me to her sisters, Josephine and Madeline. Online sleuthing revealed that others who have written about the sisters seem to know only bits and pieces of each sister’s story and no one has previously connected all the strands. Once you do, these three sisters are revealed to have been truly remarkable individuals, who led amazing lives. I will begin with a brief introduction to the family, and then take up each sister’s story in turn, though of course their lives overlapped and crisscrossed over the years.

The McLaughlin sisters included Lilian Victoria (1887-1971), Josephine (1889-1977) and Madeline Claire (1894-1984). They were all born and raised in New York, the children of Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin and Emma Rogers McLaughlin. Lilian would grow up to marry palǣontologist Barnum Brown and be a successful writer. Josephine became a very prolific Hollywood screenwriter. Madeline joined the Navy in World War I, one of the first women to do so. She was a writer as well, but didn’t live as public a life as her sisters. She did marry five times, and was the only one of the sisters to have a child.

The sisters’ father Joseph was one of 12 children born to John A. McLaughlin (ca. 1827-1900) and his wife Josephine Avezzana (1838-1923). They married in 1854. In the 1880 census, the household was living in Jersey City, New Jersey and included: John A. McLaughlin (head), age 53, who owned a liquor store; Josephine (wife), age 42; daughter Cornelia Mary (25); son Joseph A. (24, lawyer); son John A. (22, veterinary surgeon); daughter Victoria (20); son William T. (16, at school); son Lalor (14, at school); son Clifford (12, at school); daughter Felicita (10, at school); son Vincent Plowden (8, at school); daughter Pierina (4); son Leo Lawrence (2); and son Cyril Berchman (4 months).

In the 1900 census, the McLaughlin household in Manhattan was headed by Josephine (61, widowed, no occupation), and included daughter Mary, 42 and still single; son Plowden V. (27, single, dentist); daughter Felicita (28, single, school teacher); daughter Pierina (22, single, no occupation); son Leo (21, single, lawyer); son Cyril (20, single, at school), and two servants. The 1905 census (Manhattan) includes Josephine (65), Mary, Felicita, Pierina, Leo, and Cyril, as well as Josephine’s grandchildren Lilian (17) and Roy (13), and a servant. In the 1910 census (Manhattan) the household includes only Josephine, Mary, and Cyril.

Dr. Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin (1856-1895) and his wife Emma Rogers McLaughlin (1852-1911) were married sometime before the birth and death of their first child Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin, Jr., in 1885. Their daughter Lilian Victoria was born on October 31, 1887, followed by Josephine, born on July 8, 1889. Different sources gives varying dates for the births of their next two children. According to the 1905 New York State census, both Roy and Madeline were born in 1892. However, it is more likely that Madeline was born in 1894 or 1895. Joseph Sr. died in 1895, when Madeline was very young. Emma does not appear in the census for 1900, and we know she died in 1911. Thus, the girls lost both their parents relatively early in their lives. In addition, Roy disappears from online records after 1905 and seems to have died before 1910.

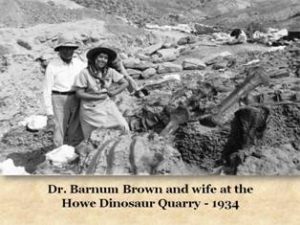

Lilian McLaughlin Brown. Lilian Victoria McLaughlin was a born story-teller. Today, she is known as the wife of “dinosaur hunter” Barnum Brown and the author of several books about her travels around the world with him looking for fossils. Her writings include an article in Natural History (1936), and three books, published between 1950 and 1956. In 2019, only I Married a Dinosaur (1950) is still in print. In Lilian’s writings, and in the biographies of Barnum Brown published by his daughter Frances (1987) and by Lowell Dingus and Mark Norell (2010), several different stories are presented about how Lilian came to meet and marry Barnum Brown. Lilian herself tells the story in the beginning of I Married a Dinosaur. Let’s look at these versions first, and then dig a little deeper using online resources to illustrate the lengths Lilian McLaughlin went to in order to “manage her brand” – long before that was a common endeavor.

On the very first page of her book, I Married a Dinosaur, Lilian misleads her readers about her first meeting with Barnum, writing:

“Having finished my schooling in an upstate New York convent, I had embarked with a graduate student group on the first leg of a world tour. The Orient – especially India – loomed large in my imagination. It loomed large also in the plans of a fellow-passenger heading a bone-digging expedition to that charmed part of the globe.” After a brief description of Barnum’s appearance and what his goals were, she jumps right to “Needless to say, we had quite a time getting a camel-caravan together for our enterprise.”

The reader gets the impression that Lilian is a naïve young school girl, having just graduated from a convent school. She heads across the ocean with a group of fellow students and just happens to encounter and fall in love with Barnum Brown while on board ship. Suddenly, they are married and setting out to hunt fossils in the Siwalik Hills of India. In reality, this is not exactly an accurate account!

Barnum’s daughter Frances provides a different version of the story of Barnum and Lilian’s romance. Barnum’s first wife Marion had died of scarlet fever in 1910, leaving toddler Frances to be raised by her maternal grandparents, and leaving Barnum as an eminently eligible – and apparently charming, charismatic, and flirtatious – bachelor. In her 1987 biography of her father, Let’s Call Him Barnum, Frances claims that Barnum met Lillian in New York, but only reconnected with her in 1921 after he had reached India following his explorations in Abyssinia in 1920 and 1921. Frances writes:

“The journey from Abyssinia to India must have been relatively uneventful, for Barnum never recounted any episodes that had stuck in his memory. . . . It was after he was well into his work in India that he received word of the impending arrival of the very personable young women he had met and liked in New York before he left for England. City-born and convent-bred Lilian Victoria McLaughlin was supposedly on a world tour with an aunt. The more likely scenario was that she, like others before her, had decided back in New York that Barnum was the husband she wanted, and, if he would not come after her, she would go after him, even if it meant crossing a couple of continents to do so. Now, more than ten years after Marion’s death, Barnum was a world away, tired of being lonely, and ripe for the plucking. He went into Calcutta to meet Lilian and quickly decided to make her his wife.” (Brown, 1987, p. 35).

In Dingus and Norell’s account (2010), we get yet another version, based in part on letters Lilian wrote to her sisters while hanging out in Egypt in 1921. Lilian is introduced, and her connection to Barnum Brown is described as follows:

“As Brown wrapped up his expedition [to Abyssinia in 1921], a vivacious, aristocratic twenty-one-year-old from New York, Lilian McLaughlin, ostensibly on a world tour with her aunt, was traveling through Egypt and awaiting Barnum’s arrival. The pair had met several years previously in New York before Barnum departed for England to begin the Abyssinian project. . . . Lilian may have harbored an ulterior motive in her pursuit of Barnum. Fancying herself a budding writer, she intended to serialize her experiences and adventures in magazine articles and possibly even books, and Barnum could certainly provide a ticket for exotic exploration.” (Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 170).

In reality, none of these versions are accurate. Lilian and Barnum had known each other, and travelled extensively together, for several years before their marriage in 1922. One can certainly understand why Lilian wanted to create an “origin story” that would present her in a more flattering light, in keeping with the mores of the time. She didn’t want to admit her actual age, the fact that she had been married before and was in the process of getting a divorce in 1921, or that she was living with Barnum before they got married. Frances may not have known the full story, or she may have simply gone along with most of Lilian’s version. Dingus and Norell (2010) were able to fill in some details based on Lilian’s letters to her sisters, housed in the archives of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. They knew, for instance, that Lilian was in Egypt in 1920 expecting to meet up with Barnum. But even they were not aware of the extent of Lilian’s misrepresentations. Certainly, Lilian would have had no way of knowing that, 100 years later, evidence of her and Barnum’s duplicity would be freely available via the interwebs to anyone who knew where and how to hunt for it.

So, what can we say, based on information gleaned from online resources in 2019? Let’s begin with Lilian’s age. Lilian McLaughlin was born on October 31, 1887. In various circumstances across the years, she would claim other birth years, though always sticking to October 31st. In the 1890 New York City Police Census, she is listed as being four years old. Her sister Josephine is listed as being one in the same census. In the 1905 State Census for New York, Lilian is listed as being 17 years old and living in Manhattan with her widowed grandmother Josephine McLaughlin, three aunts, two uncles, and her brother Roy, age 13. At the time, Lilian was attending “high school” according to the census. In the same census, Lilian’s younger sisters Josephine and Madeline (ages 16 and 13, respectively) were attending school at the Roman Catholic Academy of the Sacred Heart in Albany, New York (not to be confused with the Albany Academy, a private non-religious school for girls in the same town). There is no record of Lilian having attended the Academy of the Sacred Heart, though she certainly may have.

In the 1910 US federal census, Lilian McLaughlin (white, age 22, single, from New York) is listed as working as a clerk at the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium in Wallingford, Connecticut. Gaylord Farm was a tuberculosis hospital. Her mother, Emma Rogers McLaughlin, was a patient there in the 1910 census. Emma doesn’t appear in any 1900 census, but she wasn’t living in the household that included her mother-in-law or her children Lilian and Roy. She may already have been at Gaylord, or some other tuberculosis facility. In the 1910 census, Emma is described as a 58-year-old widow from New York, with 3 children (suggesting that Roy died before 1910). Emma died in 1911, probably from tuberculosis, and was buried in Yonkers, New York. It isn’t known how long Lilian worked at Gaylord Farm before or after her mother’s death in 1911. In the 1915 New York State Census, Lilian, 28, is working as a bookkeeper and living as a lodger in a household that included eight other lodgers. It was about this time that her two younger sisters emigrated to California.

Lilian disappears from view until 1917. On February 14, 1917, the New York Times published a list of individuals who had passed a Civil Service Exam for “clerk, first grade, female.” Near the top of the list of 153 names is that of “Lillian P. McLaughlin” (Frances says Lilian’s middle name was Victoria, so this may be a typo, or perhaps it isn’t the same Lilian).

In July of 1918, Barnum Brown was in Havana, where he got an emergency passport to return to the United States. From July 21 to 25, he travelled alone on the S.S. Mexico from Havana to New York City. Once back in New York City, Barnum applied for a regular passport to travel to Cuba, Central America, and Chile. A letter from the American Museum of Natural History supported his application, which was issued on August 20, 1918 (see below). We know from one of Marjorie O’Connell’s letters that Barnum was in Pittsburgh in October of 1918, telling Marjorie over dinner how much he had loved his wife Marion.

In May of 1919, we know that Barnum was in Texas, because that is when he proposed to Margaret Salt, the woman who would sue him for breach of promise later that fall. This is the woman Lilian would refer to in a letter as “Texas.” In August of 1919, he was back in Cuba, looking for fossils.

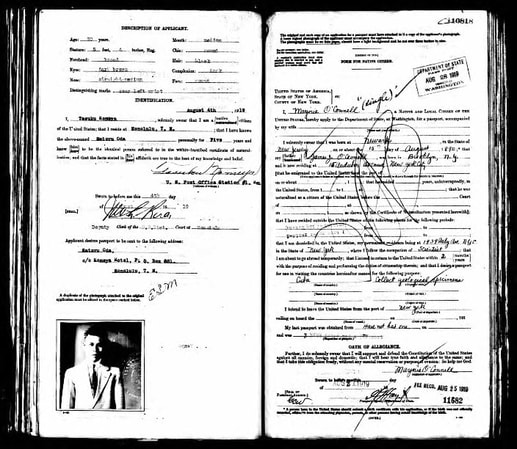

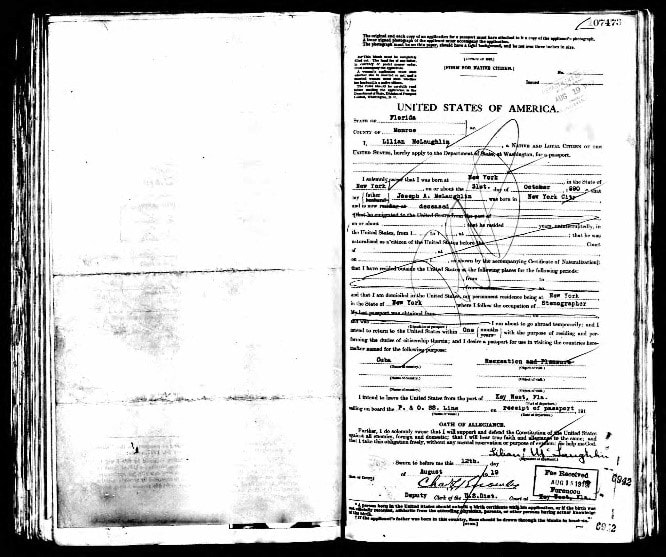

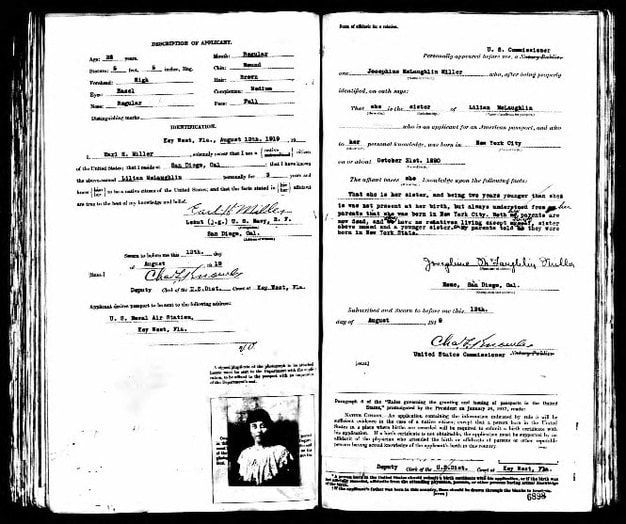

On August 12, 1919, Lilian was in Key West, Florida, applying for a US passport to travel to Cuba. On her passport application (see below) she lists her usual occupation as “stenographer,” and the purpose of her trip as “recreation and pleasure.” Because both of her parents were deceased, she had to have some other relative attest to who she was and when and where she was born. The application was signed by Josephine McLaughlin Miller (Lilian’s sister) and Earl H. Miller (Josephine’s first husband, Lilian’s brother-in-law). Earl and Josephine Miller were in Key West, Florida because Earl was in the US Navy and had been stationed there to study dirigibles (of all things). The passport was issued on August 19, 1919 (see below).

Presumably, Lilian took advantage of the fact that the Millers were in Key West so she could obtain a passport. The passport application says, in part:

“Personally appeared before me one ___ Josephine McLaughlin Miller___ who, after being properly identified, on oath says: That ___she___ is the ___sister___ of ___Lilian McLaughlin___ who is an applicant for an American passport, and who to ___her___ personal knowledge, was born in ___New York City___ on or about ___October 31st, 1890___. The officiant bases ___she___ (sic) knowledge upon the following facts: ___That she is her sister, and being two years younger than she is was not present at her birth, but always understood from her parents that she was born in New York City. Both her parents are now dead, and have no relatives living except herself, sister above named and a younger sister. Her parents told her they were born in New York State___.”

The form is signed by Josephine McLaughlin Miller, whose home is in San Diego, California. On the facing page, Earl H. Miller, also of San Diego, attests that he has known the applicant (Lilian) for three years and knows her to be a citizen of the United States and that the facts in the application are “true to the best of my knowledge and belief.”

On the application, Lilian is described as being 28, with a height of 5’5”, a high forehead, hazel eyes, a regular nose and mouth, a round chin, brown hair, and a full face. There is a standard passport photo attached. Lilian has filled out the application saying that she usually lives in New York and has come to Key West to obtain a passport and set sail to Cuba.

Of course, it wasn’t true that Josephine, Lilian, and Madeline had no other living relatives, as claimed on the passport application – there were plenty of aunts and uncles (including whichever “aunt” it was who supposedly later travelled with Lilian and Barnum as a chaperone – although one suspects this aunt may have been entirely fictitious). Even their paternal grandmother, Josephine McLaughlin (the elder) was still alive in 1919 – she didn’t die until 1923! And of course, Lilian was born in 1887, not 1890 as she claimed on this application.

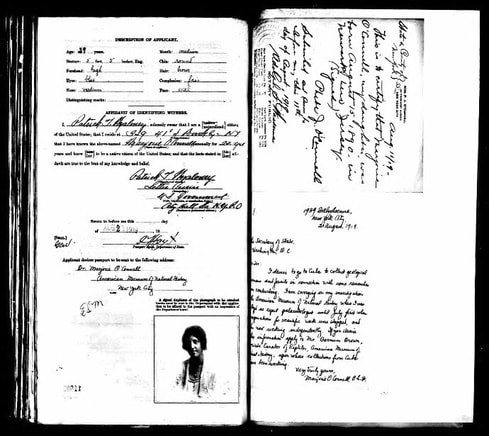

Intriguingly, on August 21, 1919, just nine days after Lilian applied for a passport to go to Cuba, Marjorie O’Connell also applied for a passport to travel to Cuba to “collect geological specimens.” Marjorie was living in New York City, but applied through the passport office in Washington, D.C. She writes that she has been working on Barnum Brown’s collections at the AMNH until July 1, 1919 and is now working independently. She says that the passport office can contact Barnum for a reference. So apparently, she knew that Barnum was in Cuba hunting fossils that summer, but she did not join him. Perhaps he discouraged her, knowing that Lilian was on her way to visit him. It was the fossil ammonites he collected on his several trips to Cuba in 1918 and 1919 that Marjorie would work on for five months at the AMNH in the fall of 1920, while she was penning her “Dear Pal” letters to him as he travelled through Abyssinia.

I could find no record of when and how Lilian travelled to Cuba after receiving her passport, but she apparently met up with Barnum there. They returned to the US together, travelling from Havana to Key West on October 11, 1919 on the S.S. Governor Cobb. The ship’s passenger list includes Barnum Brown, age 45, and Lilian McLaughlin, age 28. Just a few weeks later, the stories about Margaret Salt’s lawsuit were published in papers across the country.

Approximately six months after returning from Cuba, both Barnum Brown and Lilian McLaughlin left New York City on the S.S. Philadelphia bound for England. I couldn’t find the passenger manifests for the S.S. Philadelphia, and it’s difficult to tell which of the various dates found in different sources are accurate, if any. Thus, it isn’t clear if they travelled together.

According to one of Marjorie O’Connell’s letters, Barnum sailed for London on April 17th on the S.S. Philadelphia – her first letter to him was written that day, and a letter from Marjorie dated April 24th says he had departed one week earlier. Later, Marjorie reports that she has read in the paper that Barnum’s ship has docked in Cherbourg, France on April 29. Lilian claims she left on April 27th, for Southampton, also on the S.S. Philadelphia. On a later passport application (1924), Barnum states that he left New York on May 1, 1920.

Barnum and Lilian must have parted ways in England or France, as Barnum did not take Lilian along on his travels to Abyssinia. From letters to her sisters, we know that Lilian spent some time in Cairo, Egypt, at least from December 1920 through May of 1921, waiting for Barnum to return from his fossil- and oil-prospecting trip. Barnum’s colleagues and his father-in-law (also named Mr. Brown) had nearly given up hope of hearing from him again, when he turned up in May (whether in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia or Cairo, Egypt isn’t clear). In early June, Barnum wrote to Dr. Osborn at the AMNH wondering whether he should return to New York to take care of Margaret Salt’s court case that was still pending against him, or travel on to India to look for more fossils, as the museum wanted him to do (cited in Dingus and Norell, 2010:171-172). The decision was that he should go to India.

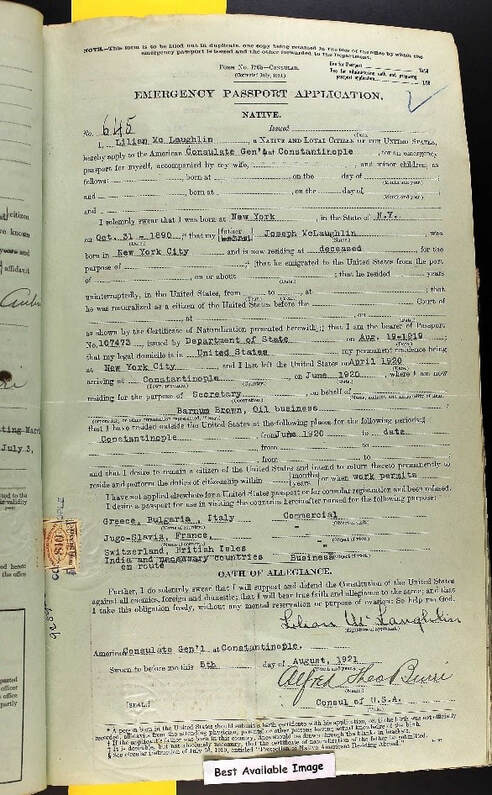

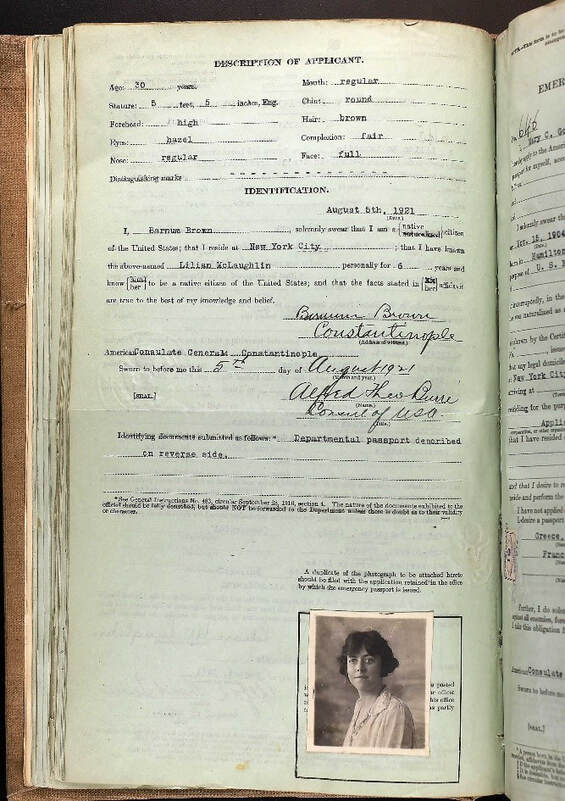

By the end of June, 1921, both Barnum and Lilian were in Constantinople, Turkey [known as Istanbul after 1930]. There, Lilian applied for a new passport to replace the one she got in 1919 in Key West. On her application, she claimed that she was Barnum Brown’s “secretary,” and that she left the United States in April of 1920 and arrived in Turkey in June of 1920 (off by one year). On this document, Barnum attests that he has known her for six years (since 1915). Once her passport was issued on August 5, 1921, the pair returned to London briefly. Their marriage had been delayed while they awaited several things. First, Lilian needed to go to London to obtain the final divorce papers from her first husband (whose identity has apparently been lost to history). Second, Barnum was waiting for approval of his marriage to Lilian from his first father-in-law. Third, Barnum met with the president the AMNH, Henry Fairfield Osborn, in London to give an accounting of his work in Abyssinia and to make plans for the work in India.

On September first, in London, Barnum applied for a passport to go to Europe and Asia. This passport has an addendum that says it was modified in 1923 in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to include travel to Egypt.

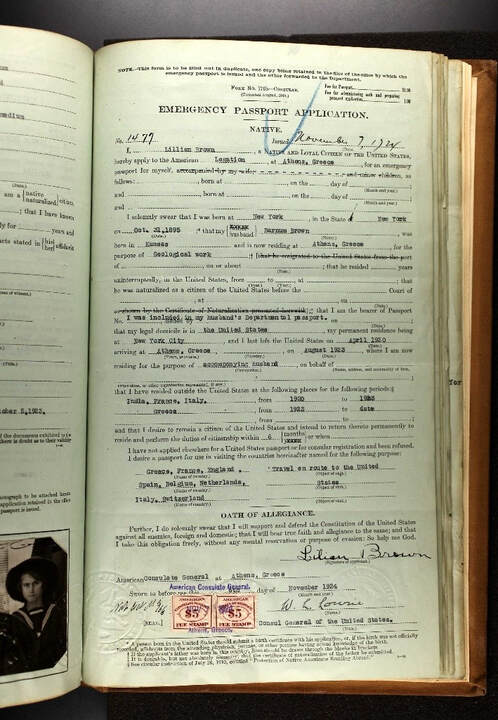

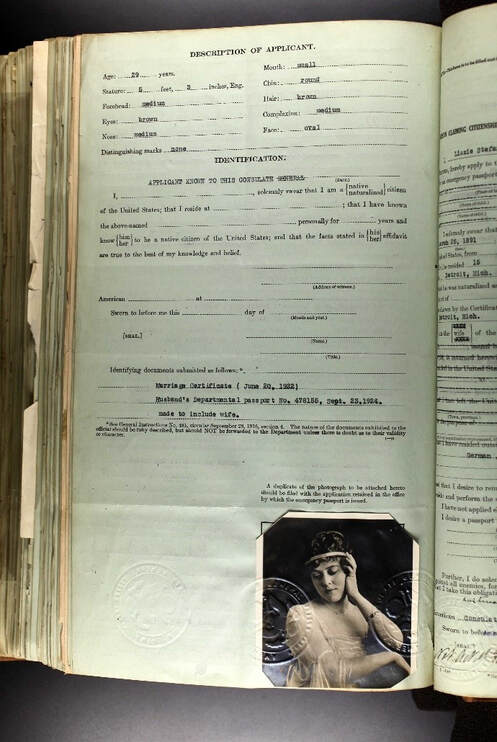

In the fall of 1921, the pair travelled from London to Bombay and then on to Calcutta, India, arriving on December 16, 1921. They didn’t get married until June 20, 1922, in Calcutta and then went off to the hinterlands to search for fossils. After fossil hunting in India and Burma, they headed to Greece, arriving in Athens on August 18, 1923. They remained in Greece for a year and a half before returning to New York City on December 31, 1924 on the S.S. Aquitania. Lilian had to get yet another passport in Greece in 1924, showing that she was now Barnum’s wife. This is the passport with the coy/corny pose instead of a standard passport photo (see below).

Lilian and Barnum Brown’s married life has been amply documented in her writings, and in the biographies of Barnum Brown by his daughter Frances Brown (1987) and by Dingus and Norell (2010). Lilian travelled all over the world with Barnum, running the field camp, hanging out with the locals, and generally having adventures and enjoying herself. She was quite successful as a published writer. The Browns never had any children, although Barnum’s daughter Frances apparently spent time with them during her school vacations and on other occasions.

While conducting research on the life of Marjorie O’Connell (Shearon), I had the opportunity to transcribe a series of letters she wrote to palǣontologist Barnum Brown in 1920, while he was off searching for oil and fossils in Abyssinia. That led me to looking into his life story, which led me to his second wife, Lilian, which led me to her sisters, Josephine and Madeline. Online sleuthing revealed that others who have written about the sisters seem to know only bits and pieces of each sister’s story and no one has previously connected all the strands. Once you do, these three sisters are revealed to have been truly remarkable individuals, who led amazing lives. I will begin with a brief introduction to the family, and then take up each sister’s story in turn, though of course their lives overlapped and crisscrossed over the years.

The McLaughlin sisters included Lilian Victoria (1887-1971), Josephine (1889-1977) and Madeline Claire (1894-1984). They were all born and raised in New York, the children of Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin and Emma Rogers McLaughlin. Lilian would grow up to marry palǣontologist Barnum Brown and be a successful writer. Josephine became a very prolific Hollywood screenwriter. Madeline joined the Navy in World War I, one of the first women to do so. She was a writer as well, but didn’t live as public a life as her sisters. She did marry five times, and was the only one of the sisters to have a child.

The sisters’ father Joseph was one of 12 children born to John A. McLaughlin (ca. 1827-1900) and his wife Josephine Avezzana (1838-1923). They married in 1854. In the 1880 census, the household was living in Jersey City, New Jersey and included: John A. McLaughlin (head), age 53, who owned a liquor store; Josephine (wife), age 42; daughter Cornelia Mary (25); son Joseph A. (24, lawyer); son John A. (22, veterinary surgeon); daughter Victoria (20); son William T. (16, at school); son Lalor (14, at school); son Clifford (12, at school); daughter Felicita (10, at school); son Vincent Plowden (8, at school); daughter Pierina (4); son Leo Lawrence (2); and son Cyril Berchman (4 months).

In the 1900 census, the McLaughlin household in Manhattan was headed by Josephine (61, widowed, no occupation), and included daughter Mary, 42 and still single; son Plowden V. (27, single, dentist); daughter Felicita (28, single, school teacher); daughter Pierina (22, single, no occupation); son Leo (21, single, lawyer); son Cyril (20, single, at school), and two servants. The 1905 census (Manhattan) includes Josephine (65), Mary, Felicita, Pierina, Leo, and Cyril, as well as Josephine’s grandchildren Lilian (17) and Roy (13), and a servant. In the 1910 census (Manhattan) the household includes only Josephine, Mary, and Cyril.

Dr. Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin (1856-1895) and his wife Emma Rogers McLaughlin (1852-1911) were married sometime before the birth and death of their first child Joseph Avezzana McLaughlin, Jr., in 1885. Their daughter Lilian Victoria was born on October 31, 1887, followed by Josephine, born on July 8, 1889. Different sources gives varying dates for the births of their next two children. According to the 1905 New York State census, both Roy and Madeline were born in 1892. However, it is more likely that Madeline was born in 1894 or 1895. Joseph Sr. died in 1895, when Madeline was very young. Emma does not appear in the census for 1900, and we know she died in 1911. Thus, the girls lost both their parents relatively early in their lives. In addition, Roy disappears from online records after 1905 and seems to have died before 1910.

Lilian McLaughlin Brown. Lilian Victoria McLaughlin was a born story-teller. Today, she is known as the wife of “dinosaur hunter” Barnum Brown and the author of several books about her travels around the world with him looking for fossils. Her writings include an article in Natural History (1936), and three books, published between 1950 and 1956. In 2019, only I Married a Dinosaur (1950) is still in print. In Lilian’s writings, and in the biographies of Barnum Brown published by his daughter Frances (1987) and by Lowell Dingus and Mark Norell (2010), several different stories are presented about how Lilian came to meet and marry Barnum Brown. Lilian herself tells the story in the beginning of I Married a Dinosaur. Let’s look at these versions first, and then dig a little deeper using online resources to illustrate the lengths Lilian McLaughlin went to in order to “manage her brand” – long before that was a common endeavor.

On the very first page of her book, I Married a Dinosaur, Lilian misleads her readers about her first meeting with Barnum, writing:

“Having finished my schooling in an upstate New York convent, I had embarked with a graduate student group on the first leg of a world tour. The Orient – especially India – loomed large in my imagination. It loomed large also in the plans of a fellow-passenger heading a bone-digging expedition to that charmed part of the globe.” After a brief description of Barnum’s appearance and what his goals were, she jumps right to “Needless to say, we had quite a time getting a camel-caravan together for our enterprise.”

The reader gets the impression that Lilian is a naïve young school girl, having just graduated from a convent school. She heads across the ocean with a group of fellow students and just happens to encounter and fall in love with Barnum Brown while on board ship. Suddenly, they are married and setting out to hunt fossils in the Siwalik Hills of India. In reality, this is not exactly an accurate account!

Barnum’s daughter Frances provides a different version of the story of Barnum and Lilian’s romance. Barnum’s first wife Marion had died of scarlet fever in 1910, leaving toddler Frances to be raised by her maternal grandparents, and leaving Barnum as an eminently eligible – and apparently charming, charismatic, and flirtatious – bachelor. In her 1987 biography of her father, Let’s Call Him Barnum, Frances claims that Barnum met Lillian in New York, but only reconnected with her in 1921 after he had reached India following his explorations in Abyssinia in 1920 and 1921. Frances writes:

“The journey from Abyssinia to India must have been relatively uneventful, for Barnum never recounted any episodes that had stuck in his memory. . . . It was after he was well into his work in India that he received word of the impending arrival of the very personable young women he had met and liked in New York before he left for England. City-born and convent-bred Lilian Victoria McLaughlin was supposedly on a world tour with an aunt. The more likely scenario was that she, like others before her, had decided back in New York that Barnum was the husband she wanted, and, if he would not come after her, she would go after him, even if it meant crossing a couple of continents to do so. Now, more than ten years after Marion’s death, Barnum was a world away, tired of being lonely, and ripe for the plucking. He went into Calcutta to meet Lilian and quickly decided to make her his wife.” (Brown, 1987, p. 35).

In Dingus and Norell’s account (2010), we get yet another version, based in part on letters Lilian wrote to her sisters while hanging out in Egypt in 1921. Lilian is introduced, and her connection to Barnum Brown is described as follows:

“As Brown wrapped up his expedition [to Abyssinia in 1921], a vivacious, aristocratic twenty-one-year-old from New York, Lilian McLaughlin, ostensibly on a world tour with her aunt, was traveling through Egypt and awaiting Barnum’s arrival. The pair had met several years previously in New York before Barnum departed for England to begin the Abyssinian project. . . . Lilian may have harbored an ulterior motive in her pursuit of Barnum. Fancying herself a budding writer, she intended to serialize her experiences and adventures in magazine articles and possibly even books, and Barnum could certainly provide a ticket for exotic exploration.” (Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 170).

In reality, none of these versions are accurate. Lilian and Barnum had known each other, and travelled extensively together, for several years before their marriage in 1922. One can certainly understand why Lilian wanted to create an “origin story” that would present her in a more flattering light, in keeping with the mores of the time. She didn’t want to admit her actual age, the fact that she had been married before and was in the process of getting a divorce in 1921, or that she was living with Barnum before they got married. Frances may not have known the full story, or she may have simply gone along with most of Lilian’s version. Dingus and Norell (2010) were able to fill in some details based on Lilian’s letters to her sisters, housed in the archives of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. They knew, for instance, that Lilian was in Egypt in 1920 expecting to meet up with Barnum. But even they were not aware of the extent of Lilian’s misrepresentations. Certainly, Lilian would have had no way of knowing that, 100 years later, evidence of her and Barnum’s duplicity would be freely available via the interwebs to anyone who knew where and how to hunt for it.

So, what can we say, based on information gleaned from online resources in 2019? Let’s begin with Lilian’s age. Lilian McLaughlin was born on October 31, 1887. In various circumstances across the years, she would claim other birth years, though always sticking to October 31st. In the 1890 New York City Police Census, she is listed as being four years old. Her sister Josephine is listed as being one in the same census. In the 1905 State Census for New York, Lilian is listed as being 17 years old and living in Manhattan with her widowed grandmother Josephine McLaughlin, three aunts, two uncles, and her brother Roy, age 13. At the time, Lilian was attending “high school” according to the census. In the same census, Lilian’s younger sisters Josephine and Madeline (ages 16 and 13, respectively) were attending school at the Roman Catholic Academy of the Sacred Heart in Albany, New York (not to be confused with the Albany Academy, a private non-religious school for girls in the same town). There is no record of Lilian having attended the Academy of the Sacred Heart, though she certainly may have.

In the 1910 US federal census, Lilian McLaughlin (white, age 22, single, from New York) is listed as working as a clerk at the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium in Wallingford, Connecticut. Gaylord Farm was a tuberculosis hospital. Her mother, Emma Rogers McLaughlin, was a patient there in the 1910 census. Emma doesn’t appear in any 1900 census, but she wasn’t living in the household that included her mother-in-law or her children Lilian and Roy. She may already have been at Gaylord, or some other tuberculosis facility. In the 1910 census, Emma is described as a 58-year-old widow from New York, with 3 children (suggesting that Roy died before 1910). Emma died in 1911, probably from tuberculosis, and was buried in Yonkers, New York. It isn’t known how long Lilian worked at Gaylord Farm before or after her mother’s death in 1911. In the 1915 New York State Census, Lilian, 28, is working as a bookkeeper and living as a lodger in a household that included eight other lodgers. It was about this time that her two younger sisters emigrated to California.

Lilian disappears from view until 1917. On February 14, 1917, the New York Times published a list of individuals who had passed a Civil Service Exam for “clerk, first grade, female.” Near the top of the list of 153 names is that of “Lillian P. McLaughlin” (Frances says Lilian’s middle name was Victoria, so this may be a typo, or perhaps it isn’t the same Lilian).

In July of 1918, Barnum Brown was in Havana, where he got an emergency passport to return to the United States. From July 21 to 25, he travelled alone on the S.S. Mexico from Havana to New York City. Once back in New York City, Barnum applied for a regular passport to travel to Cuba, Central America, and Chile. A letter from the American Museum of Natural History supported his application, which was issued on August 20, 1918 (see below). We know from one of Marjorie O’Connell’s letters that Barnum was in Pittsburgh in October of 1918, telling Marjorie over dinner how much he had loved his wife Marion.

In May of 1919, we know that Barnum was in Texas, because that is when he proposed to Margaret Salt, the woman who would sue him for breach of promise later that fall. This is the woman Lilian would refer to in a letter as “Texas.” In August of 1919, he was back in Cuba, looking for fossils.

On August 12, 1919, Lilian was in Key West, Florida, applying for a US passport to travel to Cuba. On her passport application (see below) she lists her usual occupation as “stenographer,” and the purpose of her trip as “recreation and pleasure.” Because both of her parents were deceased, she had to have some other relative attest to who she was and when and where she was born. The application was signed by Josephine McLaughlin Miller (Lilian’s sister) and Earl H. Miller (Josephine’s first husband, Lilian’s brother-in-law). Earl and Josephine Miller were in Key West, Florida because Earl was in the US Navy and had been stationed there to study dirigibles (of all things). The passport was issued on August 19, 1919 (see below).

Presumably, Lilian took advantage of the fact that the Millers were in Key West so she could obtain a passport. The passport application says, in part:

“Personally appeared before me one ___ Josephine McLaughlin Miller___ who, after being properly identified, on oath says: That ___she___ is the ___sister___ of ___Lilian McLaughlin___ who is an applicant for an American passport, and who to ___her___ personal knowledge, was born in ___New York City___ on or about ___October 31st, 1890___. The officiant bases ___she___ (sic) knowledge upon the following facts: ___That she is her sister, and being two years younger than she is was not present at her birth, but always understood from her parents that she was born in New York City. Both her parents are now dead, and have no relatives living except herself, sister above named and a younger sister. Her parents told her they were born in New York State___.”

The form is signed by Josephine McLaughlin Miller, whose home is in San Diego, California. On the facing page, Earl H. Miller, also of San Diego, attests that he has known the applicant (Lilian) for three years and knows her to be a citizen of the United States and that the facts in the application are “true to the best of my knowledge and belief.”

On the application, Lilian is described as being 28, with a height of 5’5”, a high forehead, hazel eyes, a regular nose and mouth, a round chin, brown hair, and a full face. There is a standard passport photo attached. Lilian has filled out the application saying that she usually lives in New York and has come to Key West to obtain a passport and set sail to Cuba.

Of course, it wasn’t true that Josephine, Lilian, and Madeline had no other living relatives, as claimed on the passport application – there were plenty of aunts and uncles (including whichever “aunt” it was who supposedly later travelled with Lilian and Barnum as a chaperone – although one suspects this aunt may have been entirely fictitious). Even their paternal grandmother, Josephine McLaughlin (the elder) was still alive in 1919 – she didn’t die until 1923! And of course, Lilian was born in 1887, not 1890 as she claimed on this application.

Intriguingly, on August 21, 1919, just nine days after Lilian applied for a passport to go to Cuba, Marjorie O’Connell also applied for a passport to travel to Cuba to “collect geological specimens.” Marjorie was living in New York City, but applied through the passport office in Washington, D.C. She writes that she has been working on Barnum Brown’s collections at the AMNH until July 1, 1919 and is now working independently. She says that the passport office can contact Barnum for a reference. So apparently, she knew that Barnum was in Cuba hunting fossils that summer, but she did not join him. Perhaps he discouraged her, knowing that Lilian was on her way to visit him. It was the fossil ammonites he collected on his several trips to Cuba in 1918 and 1919 that Marjorie would work on for five months at the AMNH in the fall of 1920, while she was penning her “Dear Pal” letters to him as he travelled through Abyssinia.

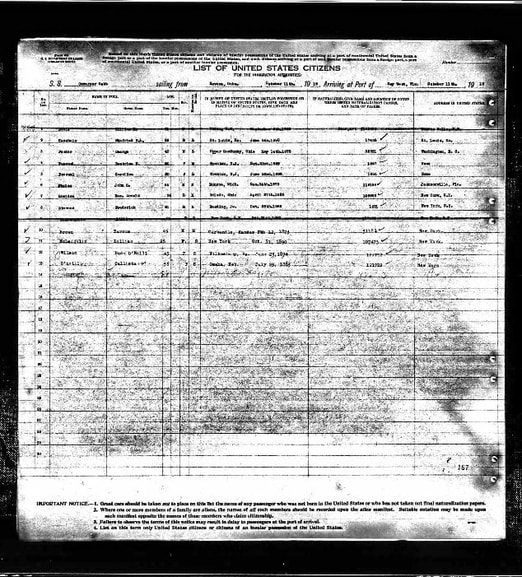

I could find no record of when and how Lilian travelled to Cuba after receiving her passport, but she apparently met up with Barnum there. They returned to the US together, travelling from Havana to Key West on October 11, 1919 on the S.S. Governor Cobb. The ship’s passenger list includes Barnum Brown, age 45, and Lilian McLaughlin, age 28. Just a few weeks later, the stories about Margaret Salt’s lawsuit were published in papers across the country.

Approximately six months after returning from Cuba, both Barnum Brown and Lilian McLaughlin left New York City on the S.S. Philadelphia bound for England. I couldn’t find the passenger manifests for the S.S. Philadelphia, and it’s difficult to tell which of the various dates found in different sources are accurate, if any. Thus, it isn’t clear if they travelled together.

According to one of Marjorie O’Connell’s letters, Barnum sailed for London on April 17th on the S.S. Philadelphia – her first letter to him was written that day, and a letter from Marjorie dated April 24th says he had departed one week earlier. Later, Marjorie reports that she has read in the paper that Barnum’s ship has docked in Cherbourg, France on April 29. Lilian claims she left on April 27th, for Southampton, also on the S.S. Philadelphia. On a later passport application (1924), Barnum states that he left New York on May 1, 1920.

Barnum and Lilian must have parted ways in England or France, as Barnum did not take Lilian along on his travels to Abyssinia. From letters to her sisters, we know that Lilian spent some time in Cairo, Egypt, at least from December 1920 through May of 1921, waiting for Barnum to return from his fossil- and oil-prospecting trip. Barnum’s colleagues and his father-in-law (also named Mr. Brown) had nearly given up hope of hearing from him again, when he turned up in May (whether in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia or Cairo, Egypt isn’t clear). In early June, Barnum wrote to Dr. Osborn at the AMNH wondering whether he should return to New York to take care of Margaret Salt’s court case that was still pending against him, or travel on to India to look for more fossils, as the museum wanted him to do (cited in Dingus and Norell, 2010:171-172). The decision was that he should go to India.

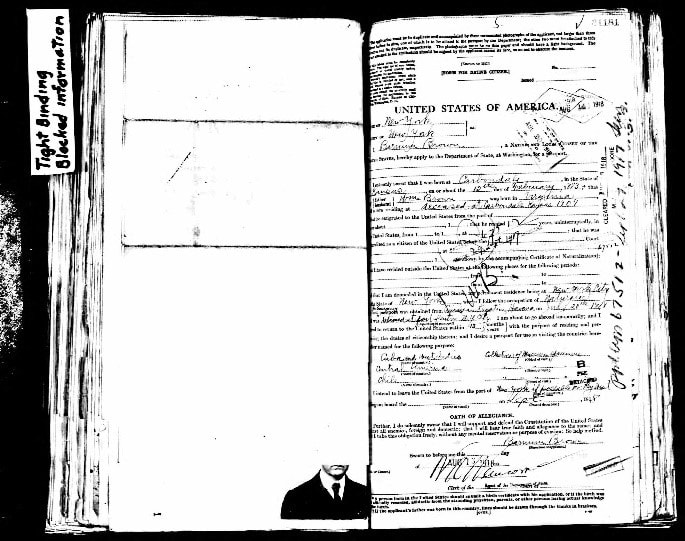

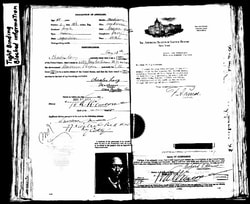

By the end of June, 1921, both Barnum and Lilian were in Constantinople, Turkey [known as Istanbul after 1930]. There, Lilian applied for a new passport to replace the one she got in 1919 in Key West. On her application, she claimed that she was Barnum Brown’s “secretary,” and that she left the United States in April of 1920 and arrived in Turkey in June of 1920 (off by one year). On this document, Barnum attests that he has known her for six years (since 1915). Once her passport was issued on August 5, 1921, the pair returned to London briefly. Their marriage had been delayed while they awaited several things. First, Lilian needed to go to London to obtain the final divorce papers from her first husband (whose identity has apparently been lost to history). Second, Barnum was waiting for approval of his marriage to Lilian from his first father-in-law. Third, Barnum met with the president the AMNH, Henry Fairfield Osborn, in London to give an accounting of his work in Abyssinia and to make plans for the work in India.

On September first, in London, Barnum applied for a passport to go to Europe and Asia. This passport has an addendum that says it was modified in 1923 in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to include travel to Egypt.

In the fall of 1921, the pair travelled from London to Bombay and then on to Calcutta, India, arriving on December 16, 1921. They didn’t get married until June 20, 1922, in Calcutta and then went off to the hinterlands to search for fossils. After fossil hunting in India and Burma, they headed to Greece, arriving in Athens on August 18, 1923. They remained in Greece for a year and a half before returning to New York City on December 31, 1924 on the S.S. Aquitania. Lilian had to get yet another passport in Greece in 1924, showing that she was now Barnum’s wife. This is the passport with the coy/corny pose instead of a standard passport photo (see below).

Lilian and Barnum Brown’s married life has been amply documented in her writings, and in the biographies of Barnum Brown by his daughter Frances Brown (1987) and by Dingus and Norell (2010). Lilian travelled all over the world with Barnum, running the field camp, hanging out with the locals, and generally having adventures and enjoying herself. She was quite successful as a published writer. The Browns never had any children, although Barnum’s daughter Frances apparently spent time with them during her school vacations and on other occasions.

The passenger list from the S.S. Governor Cobb, taking Barnum and Lilian from Havana to Key West in 1919. Barnum Brown is on line 10, Lilian McLaughlin on line 11.

Lilian McLaughlin Brown’s emergency 1924 passport application in Athens, Greece, p. 1,

and p. 2, below.

Barnum Brown’s passport application in New York in August of 1918, with a letter from the AMNH, right side of image to the left, both pages of image below.

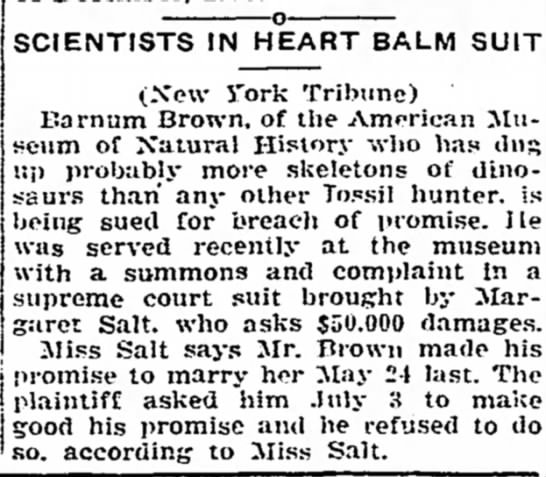

A few words about Margaret Salt, aka “Texas”. It is clear that Lilian and Barnum were already romantically involved when he met a woman named Margaret Salt in either 1918 or 1919. In letters to his superiors at the museum in 1919, he refers to the fact that he is being sued by a woman for “breach of promise” – for agreeing to marry her and then not following through. Barnum was sufficiently well-known already by this time for the court case to make the national news. In one of her letters home to her sisters, Lilian refers to this woman as “Texas.” A little on-line sleuthing turned up a few tidbits of information about Margaret Salt’s life before and after her collision with the ever-charming and charismatic Barnum Brown.

Reports of the lawsuit against Barnum for breach of promise were published in newspapers in New York, Nebraska, and Arizona (and probably others). The earliest post I discovered was from the New York Tribune on November 7, 1919. All the articles are identical, although I prefer the headline of the Arizona Republic version of December 2, 1919: “Scientists in Heart Balm Suit (New York Tribune). Barnum Brown, of the American Museum of Natural History who has dug up probably more skeletons of dinosaurs than any other fossil hunter, is being sued for breach of promise. He was served recently at the museum with a summons and complaint in a supreme court suit brought by Margaret Salt, who asks $50,000 damages. Miss Salt says Mr. Brown made his promise to marry her May 24 last. The plaintiff asked him July 3 to make good his promise and he refused to do so, according to Miss Salt.” [Image of original newspaper article below].

In 1919, Barnum was in Texas, proposing to Miss Salt on May 24th (at least, according to her). The next day he returned to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (Dingus and Norell, 2010:158). That fall he was in Cuba with Lilian. In a letter to her sisters on January 4, 1922 (from India), Lilian writes: “I love B, and I never could have stuck to him all these years, especially after the Texas affair, the keenest hurt of which was that when it came to the showdown he stood by the other woman at my expense, and to her made me the excuse for the lies and the dealings that got him into that wretched affair. B loves me too, I know, and he raises hell if I look at another man, but he carries on affairs with other women of which I have proof. There is a woman in the Museum who has been writing to him for years. When we were home he used to read me her letters, which were “Deal Pal” stuff, and once he told me he had asked her not to write him anymore. The other day by accident I found a 20 page love letter, dated November 4, 1921. It was in among some postcards and I thought of course it was an old letter, knowing her writing. Now I know perfectly well that he has no intention of marrying that woman any more than he had of marrying Texas, but he likes to string it along year after year. Texas nipped it in the bud after three weeks, otherwise he would still have been writing her too.” (Letter from Lilian to her sisters cited in Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 179).

This reference to “three weeks” (actually closer to seven) may refer to Barnum’s proposal to Margaret Salt on May 24, 1919, and her pressing him about getting married on July 3rd. It isn’t clear when the lawsuit was filed, or how it was resolved, sometime after December of 1921, but certainly Marjorie O’Connell – the author of the 1920 “Dear Pal” letters – seemed to be completely unaware of the Texas affair and the lawsuit, and unaware of Barnum’s long-standing relationship with Lilian. In Marjorie’s letter to Barnum from October 3-4, 1920, she pens a long section about whether or not he might and/or should eventually remarry. Unfortunately, only Marjorie’s letters to Barnum from 1920 have survived, so we don’t have any indication of how Marjorie felt when she heard that Barnum and Lilian had married in India in 1922.

It also seems clear from the “Dear Pal” letters themselves that while Marjorie idolized Barnum, and felt beholden to him for saving her from her darkest days of depression after her breakup from her ten-year affair with (the married) Dr. Amadeus Grabau in 1918, she wasn’t romantically/sexually “in love” with Barnum and held no delusions that he would marry her.

In Marjorie’s letters written decades later in the 1960s, she makes it clear that Dr. Grabau, whom she calls her “scientist,” was the great love of her life, and makes only a few mentions of Barnum Brown, mostly in reference to him benefitting financially from her work on his fossils. Another clue for the careful reader of all her correspondence is that she refers to Barnum as “Sphinxie” in letters to him in April and July of 1920, when she knew he was travelling through Egypt on his way to Abyssinia. Then, more than four decades later, she affectionately calls her final lover (Dr. Rufus B. Robbins), “Sphinxie” in a letter she wrote him in December of 1960.

So, who was Margaret Salt and whatever happened to her? She apparently was not successful in her lawsuit against Barnum Brown. Certainly he didn’t have $50,000 to pay her, and there is no further mention of her or the lawsuit in any newspaper articles I could find after the initial brief mentions in November and December of 1919. According to online census records, there was only one Margaret Salt living in Texas during this time period. She was the fourth of five children of Samuel and Minnie Salt of Ft. Worth, Texas. Margaret Elizabeth Salt was born in 1893. In the 1910 census, Margaret was 16, living with her parents and most of her siblings in Ft. Worth, and working as a cashier at a shoe store. The City Directory for 1911 lists her as a bookkeeper for the Ritter-Costello Company in Ft. Worth, and in 1912 she was working as a cashier for Montgomery Ward. In the 1920 census, she was still single at age 26, living at home, with no occupation listed.

Sometime before 1924, Margaret was married to Lawrence Neil McCullough, who was also from Texas and worked as a lumberman. They had a son Lawrence Neil, Jr., born in 1924, and a daughter Martha Lucille, born in 1929. They lived in Pampa, Gray County, Texas until at least 1940, and then moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Still living in Albuquerque, Lawrence Neil, Sr. died in 1957, and Margaret died in 1973. Their son Lawrence Neil McCullough, Jr., grew up to be a well-known psychiatrist, and died in 2011 in Albuquerque.

Marjorie O’Connell went on to marry the comparatively boring William Shearon, but she still led a most amazing life, albeit one that no longer involved fossil ammonites after the early 1920s. We turn now to the second of the Remarkable McLaughlin Sisters, Josephine.

This reference to “three weeks” (actually closer to seven) may refer to Barnum’s proposal to Margaret Salt on May 24, 1919, and her pressing him about getting married on July 3rd. It isn’t clear when the lawsuit was filed, or how it was resolved, sometime after December of 1921, but certainly Marjorie O’Connell – the author of the 1920 “Dear Pal” letters – seemed to be completely unaware of the Texas affair and the lawsuit, and unaware of Barnum’s long-standing relationship with Lilian. In Marjorie’s letter to Barnum from October 3-4, 1920, she pens a long section about whether or not he might and/or should eventually remarry. Unfortunately, only Marjorie’s letters to Barnum from 1920 have survived, so we don’t have any indication of how Marjorie felt when she heard that Barnum and Lilian had married in India in 1922.

It also seems clear from the “Dear Pal” letters themselves that while Marjorie idolized Barnum, and felt beholden to him for saving her from her darkest days of depression after her breakup from her ten-year affair with (the married) Dr. Amadeus Grabau in 1918, she wasn’t romantically/sexually “in love” with Barnum and held no delusions that he would marry her.

In Marjorie’s letters written decades later in the 1960s, she makes it clear that Dr. Grabau, whom she calls her “scientist,” was the great love of her life, and makes only a few mentions of Barnum Brown, mostly in reference to him benefitting financially from her work on his fossils. Another clue for the careful reader of all her correspondence is that she refers to Barnum as “Sphinxie” in letters to him in April and July of 1920, when she knew he was travelling through Egypt on his way to Abyssinia. Then, more than four decades later, she affectionately calls her final lover (Dr. Rufus B. Robbins), “Sphinxie” in a letter she wrote him in December of 1960.

So, who was Margaret Salt and whatever happened to her? She apparently was not successful in her lawsuit against Barnum Brown. Certainly he didn’t have $50,000 to pay her, and there is no further mention of her or the lawsuit in any newspaper articles I could find after the initial brief mentions in November and December of 1919. According to online census records, there was only one Margaret Salt living in Texas during this time period. She was the fourth of five children of Samuel and Minnie Salt of Ft. Worth, Texas. Margaret Elizabeth Salt was born in 1893. In the 1910 census, Margaret was 16, living with her parents and most of her siblings in Ft. Worth, and working as a cashier at a shoe store. The City Directory for 1911 lists her as a bookkeeper for the Ritter-Costello Company in Ft. Worth, and in 1912 she was working as a cashier for Montgomery Ward. In the 1920 census, she was still single at age 26, living at home, with no occupation listed.

Sometime before 1924, Margaret was married to Lawrence Neil McCullough, who was also from Texas and worked as a lumberman. They had a son Lawrence Neil, Jr., born in 1924, and a daughter Martha Lucille, born in 1929. They lived in Pampa, Gray County, Texas until at least 1940, and then moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Still living in Albuquerque, Lawrence Neil, Sr. died in 1957, and Margaret died in 1973. Their son Lawrence Neil McCullough, Jr., grew up to be a well-known psychiatrist, and died in 2011 in Albuquerque.

Marjorie O’Connell went on to marry the comparatively boring William Shearon, but she still led a most amazing life, albeit one that no longer involved fossil ammonites after the early 1920s. We turn now to the second of the Remarkable McLaughlin Sisters, Josephine.

Josephine McLaughlin (Lilian’s middle sister). Josephine was the middle McLaughlin sister, growing up in the household in NYC. She claimed at various points to have been born in 1892 or 1894, but she was actually born in 1889. In the 1890 City Police Census for New York City, she is listed as being one year of age. In 1905, she was attending the Albany Academy of the Sacred Heart, age 16, along with her sister Madeline, age 13 (or perhaps 10).

In a profile of her written in 1934, the author says she moved to California in 1915, where she lived for most of her life (Keffer, 1934:245). Over the years, Josephine would have a very successful career as a Hollywood “scenario writer” (screenwriter), marry four times (divorced twice, widowed once), and go by a wide variety of names. She died in Century City, Los Angeles County on August 24, 1977. She apparently never had children.

Josephine married her first husband, Earl Humphrey Miller, in 1916. Earl was the son of Udell/Eudell Johnson Miller and Anna Elizabeth Humphrey. He was born in 1889 in South Dakota. His father moved the family to southern California in 1903. Earl and Josephine were married on February 29, 1916 (Leap Day, a day when women traditionally are allowed to propose to men). In 1917, his WWI draft registration form shows that he is married to Josephine McLaughlin and is an attorney. Earl joined the US Navy and was assigned to Pensacola, Florida Naval Aviation Station in June of 1917. He had several other postings, including being sent ‘abroad’ from August of 1918 to January of 1919. In 1919, Earl and Josephine were stationed in Key West, where they signed the affidavit for Lilian McLaughlin to get a passport to travel to Cuba. Earl had been sent to Key West to study dirigibles. After his stint in the US Navy, where he was a Lt., J.G., Earl returned to his career an attorney and worked as a general practice attorney his entire life. In the 1920 US Federal Census, Earl H. Miller, age 28, and his wife Josephine, age 26, were living with Earl’s parents and his sister Elizabeth (Bessie), a school teacher, in San Diego.

In 1918, Josephine had begun writing and publishing love stories for magazines under the pen name “Bradley King.” By 1921, she had become well known in Hollywood for her writing skills, and was profiled in the Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual for 1921.

At some point, apparently before 1923, Josephine and Earl separated. In 1934, in Arizona, Earl got married again, to Iva Garnett Dean (1900-1964). After Iva died in 1964, Earl married a woman named Charlotte. He died on July 14, 1965 and is buried in the Ft. Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego. His third wife Charlotte survived him, as did his sister Bessie.

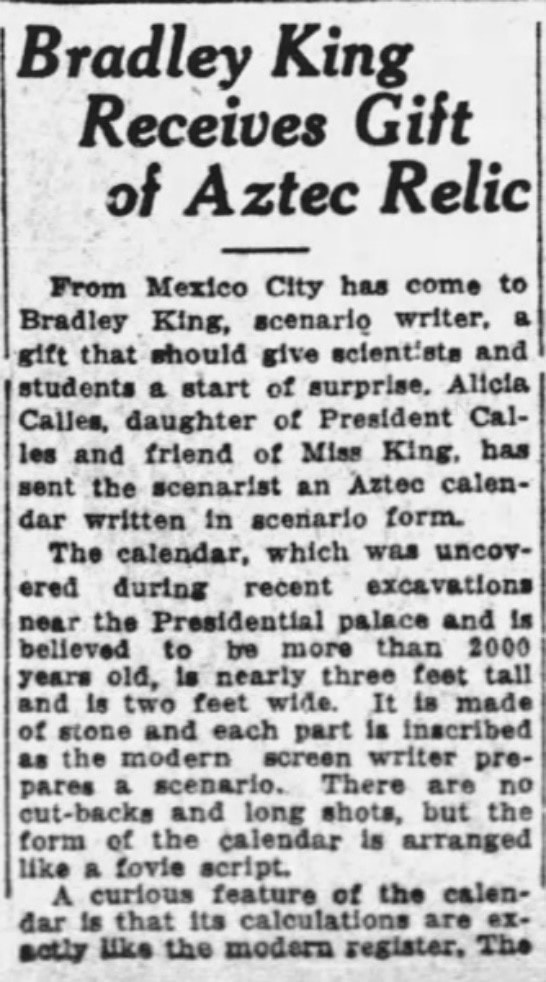

On November 5, 1923, Josephine arrived in Southampton, England on the S.S. Mauretania, out of New York, as “Bradley King, writer, age 28,” returning to New York on November 26. In 1925, she made the newspapers as the recipient of an unusual gift (see below). It was an Aztec calendar stone, but not the giant, very famous one discovered in 1790. [Original newspaper image from the Los Angeles Times, 11/15/1925, p. 69, below]

In a profile of her written in 1934, the author says she moved to California in 1915, where she lived for most of her life (Keffer, 1934:245). Over the years, Josephine would have a very successful career as a Hollywood “scenario writer” (screenwriter), marry four times (divorced twice, widowed once), and go by a wide variety of names. She died in Century City, Los Angeles County on August 24, 1977. She apparently never had children.

Josephine married her first husband, Earl Humphrey Miller, in 1916. Earl was the son of Udell/Eudell Johnson Miller and Anna Elizabeth Humphrey. He was born in 1889 in South Dakota. His father moved the family to southern California in 1903. Earl and Josephine were married on February 29, 1916 (Leap Day, a day when women traditionally are allowed to propose to men). In 1917, his WWI draft registration form shows that he is married to Josephine McLaughlin and is an attorney. Earl joined the US Navy and was assigned to Pensacola, Florida Naval Aviation Station in June of 1917. He had several other postings, including being sent ‘abroad’ from August of 1918 to January of 1919. In 1919, Earl and Josephine were stationed in Key West, where they signed the affidavit for Lilian McLaughlin to get a passport to travel to Cuba. Earl had been sent to Key West to study dirigibles. After his stint in the US Navy, where he was a Lt., J.G., Earl returned to his career an attorney and worked as a general practice attorney his entire life. In the 1920 US Federal Census, Earl H. Miller, age 28, and his wife Josephine, age 26, were living with Earl’s parents and his sister Elizabeth (Bessie), a school teacher, in San Diego.

In 1918, Josephine had begun writing and publishing love stories for magazines under the pen name “Bradley King.” By 1921, she had become well known in Hollywood for her writing skills, and was profiled in the Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual for 1921.

At some point, apparently before 1923, Josephine and Earl separated. In 1934, in Arizona, Earl got married again, to Iva Garnett Dean (1900-1964). After Iva died in 1964, Earl married a woman named Charlotte. He died on July 14, 1965 and is buried in the Ft. Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego. His third wife Charlotte survived him, as did his sister Bessie.

On November 5, 1923, Josephine arrived in Southampton, England on the S.S. Mauretania, out of New York, as “Bradley King, writer, age 28,” returning to New York on November 26. In 1925, she made the newspapers as the recipient of an unusual gift (see below). It was an Aztec calendar stone, but not the giant, very famous one discovered in 1790. [Original newspaper image from the Los Angeles Times, 11/15/1925, p. 69, below]

In 1926, Josephine, travelling again as Bradley King, was reported by the Los Angeles Times to be staying at the Savoy Hotel in London, ostensibly to visit “British literary notables.” She returned to New York via Cherbourg, sailing out of Southampton on September 6 on the S.S. Leviathan.

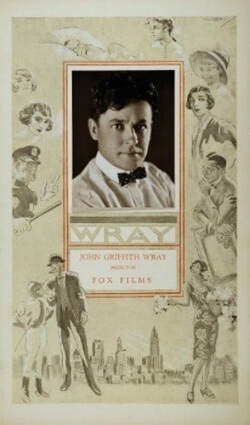

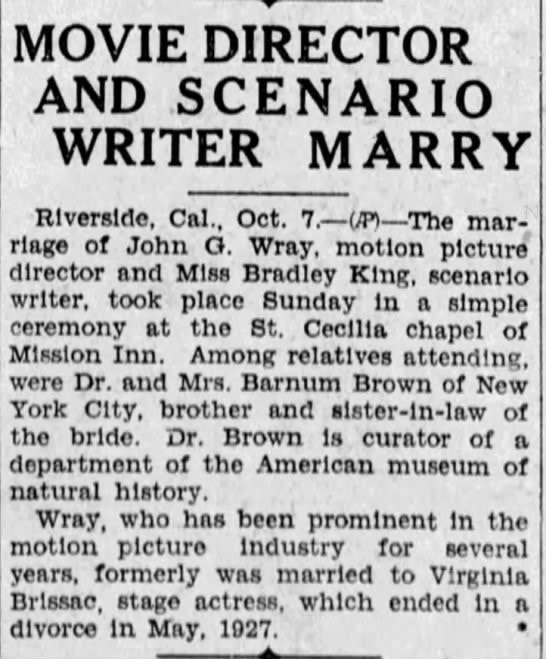

On October 6, 1928 Josephine married her second husband John Griffith Wray (1881-1929). He was a well-known director of silent films for the Thomas H. Ince Studios, and had been divorced by his previous wife, actress Virginia Brissac, in 1927.

From “Period Paper,” https://www.periodpaper.com/products/1926-fox-john-griffith-wray-silent-film-director-usabal-original-000877-fox-021

On October 6, 1928 Josephine married her second husband John Griffith Wray (1881-1929). He was a well-known director of silent films for the Thomas H. Ince Studios, and had been divorced by his previous wife, actress Virginia Brissac, in 1927.

From “Period Paper,” https://www.periodpaper.com/products/1926-fox-john-griffith-wray-silent-film-director-usabal-original-000877-fox-021

The Billings, Montana Gazette, 10/8/1928, p. 1

The Billings, Montana Gazette, 10/8/1928, p. 1

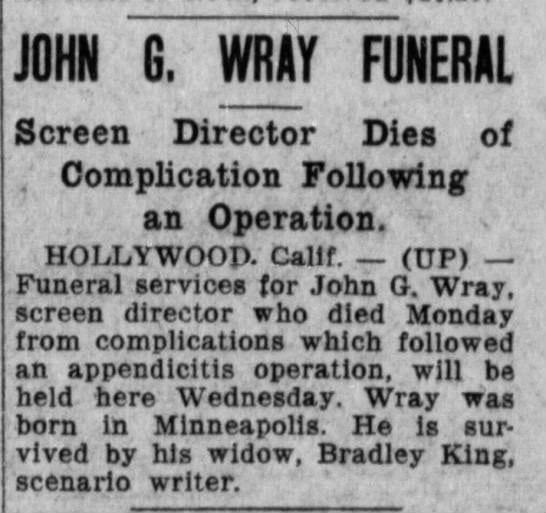

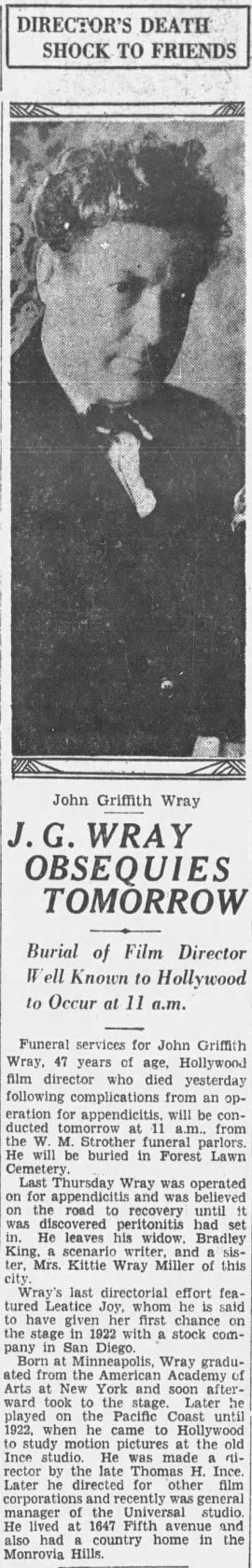

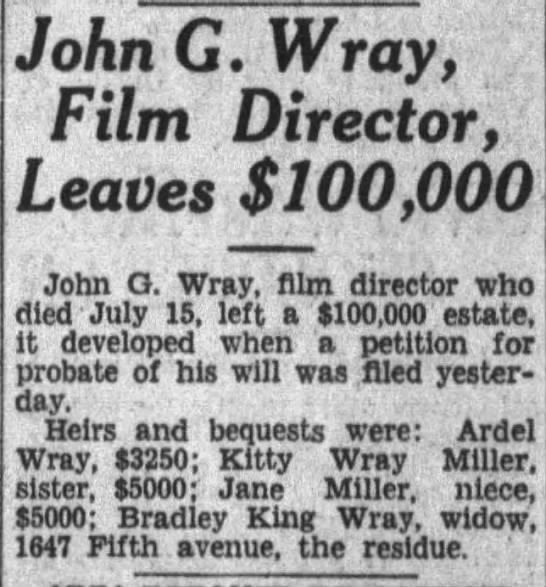

Unfortunately, on July 15, 1929, John Griffith Wray died from complications following surgery for appendicitis. He left the bulk of his $100,000 fortune to his widow, Bradley King Wray (Josephine McLaughlin). His death was reported in newspapers across the country and in Canada.

Lincoln, Nebraska Journal Star, 7/16/1929, p. 1

Los Angeles Times, 7/16/1929

Los Angeles Times, 8/10/1929

In the 1930 census, Josephine, going by “Bradley King Wray” is listed as a widow, age 36, living in Los Angeles with the family of her deceased husband John’s sister Kitty Wray Miller, age 23, and her husband Frank A. Miller, age 30 (no relation to Earl H. Miller), and Frank’s daughter from a previous relationship. “Madge Wells” (Madeline McLaughlin), age 34, is also a member of the household, listed as a “guest.” Josephine’s occupation is listed as “scenario writer,” while Madge has no occupation listed.

On March 12, 1930, Josephine traveled on the S.S. Matsonia from San Francisco to Honolulu as “Miss Bradley King of Hollywood.” Her sister Madeline and Madeline’s son Bradley accompanied her.

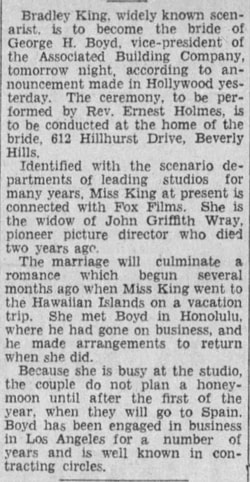

From April 10-16, 1930, she returned from Honolulu to San Francisco on the S.S. President Taft, traveling again as “Bradley King,” whose home was in Hollywood. She had met businessman George H. Boyd while in Hawaii, and they travelled back to the US together.

Josephine’s third husband was George Hiram Boyd (1896-1977), the man she met in Hawaii. They were married on October 31, 1930.

Los Angeles Times, 10/28/1930, p. 21

On March 12, 1930, Josephine traveled on the S.S. Matsonia from San Francisco to Honolulu as “Miss Bradley King of Hollywood.” Her sister Madeline and Madeline’s son Bradley accompanied her.

From April 10-16, 1930, she returned from Honolulu to San Francisco on the S.S. President Taft, traveling again as “Bradley King,” whose home was in Hollywood. She had met businessman George H. Boyd while in Hawaii, and they travelled back to the US together.

Josephine’s third husband was George Hiram Boyd (1896-1977), the man she met in Hawaii. They were married on October 31, 1930.

Los Angeles Times, 10/28/1930, p. 21

In January of 1933, Josephine traveled on the S.S. Antigua from Balboa (Panama Canal Zone), to Los Angeles as “Bradley Boyd,” age 39, accompanied by her husband “George H. Boyd,” age 36, whose home was in Van Nuys, California.

A history of the San Fernando Valley, published when Josephine lived there with her husband George H. Boyd, includes this biographical listing for Bradly King (Keffer, 1934:245-246):

“Bradley King

Bradley King, widely known fiction and motion picture writer, is one who finds enjoyment and recreation on her beautiful six-acre estate, “El Ranchito,” at 4410 Densmore Avenue, Encina, which she has occupied since 1931 with her husband, George H. Boyd, well-known contractor and builder. On this home-place, surrounded by a walnut grove, Miss King finds opportunity for the pursuit of her hobbies, which are gardening, floriculture, swimming and fine horses.

Giuseppe Avezzana McLaughlin, a physician in New York City, was Bradley King’s father. Emma (Rogers) McLaughlin, her mother, came from a Quaker family in Philadelphia. The daughter attended the Academy of the Sacred Heart, at Albany, New York. In 1915 she came to California, spending a year in San Bernardino and two years in San Diego. She started writing love stories for magazine in 1918, under the name of Bradley King. Went east for a year and travelled with her husband who was a naval officer in “Lighter than Air”, then back to San Diego in the fall of 1919. The next spring Tom Ince sent for her and she went to Culver City under contract with “Lying Lips,” after which she wrote an adaptation of “Anna Christie,” and many others until 1924. She wrote approximately 20 stories and scripts while under contract. Next followed two scripts for Warner Bros., a contract with Fox, then to England in 1926. “One Increasing Purpose” came next. In 1927 she went to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for a year and did “Mockery” and “Lovelorn”. Then to First National in 1928 where she did “Weary River”, Dick Bathelmess’ first talking picture, also “Drag” and “Song of the Gods” – approximately eight pictures in two years, all talking films.

Then occurred her marriage at Los Angeles in 1928 to Gohn (sic) Griffith Wray of Superior, Wisconsin. He died the following year and she went to Europe and various places for four months after his passing. Then back to Fox for one picture, after which she spent 1931 in travelling. During that year she was married at Los Angeles to George H. Boyd of Boston, Mass. Various studios then had her services until 1932 when she went under contract to Fox for a year. The summer of 1933 was spent in travel with her husband. Later she did “Hoopla”, but is now under contract with Universal and is doing “The Mystery of Edwin Drood” by Charles Dickens.

Miss King is a Catholic. She holds memberships in the Writers Club, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and the Dickensian Club.

Her first real estate purchase in San Fernando Valley was a 33-acre orange grove at Wells Drive, Reseda, in 1928.”

In 1938, she sold “El Ranchito” to Mickey Rooney (see below).

Oakland Tribune, 11/17/1940, p. 83, from a story titled “Home on the Range” by Lucie Neville

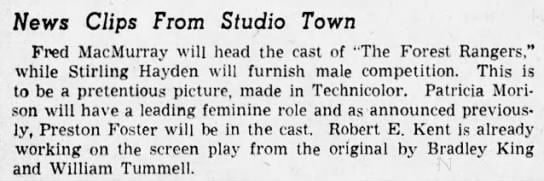

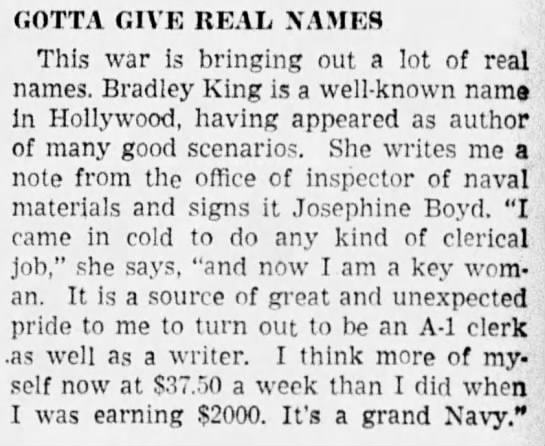

In November of 1940, Josephine and George Boyd were divorced. It is reported that he had lost much of her $400,000 fortune through poor investments. By 1941, Josephine had returned to identifying herself as “Bradley King,” as seen in this newspaper article (left).

Los Angeles Times, 5/29/1941, p. 38

In 1942, Josephine had joined the war effort, working as a clerk and giving her real name as “Josephine Boyd” (see below). Los Angeles Times, 10/3/1942, p. 20

On April 9, 1944, Josephine married for the fourth time, to Albert Crisp Windley (1898-1969). Mr. Windley had divorced a wife in 1939. In a newspaper story about a party in September of 1944, Josephine and Albert are identified as “Mr. and Mrs. Bradley King of Hollywood” (see below). Also attending the party was the cousin of the guest (Howard E. Rogers) and his wife, “Comdr. and Mrs. Joseph Ouellet.” Mrs. Ouellet was, of course, Madeline McLaughlin – Joseph Ouellet was the fourth of Madeline’s five husbands. In another citation from 1944, Josephine is going by “Bradley King Windley.” Long Beach Independent, 9/26/1944, p. 6

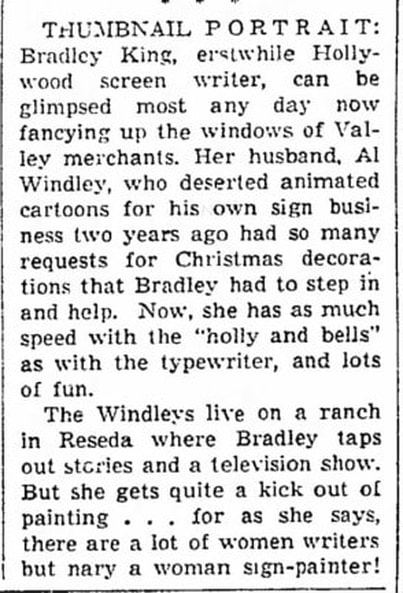

Mr. Windley worked as a notary public, a cartoonist, and a sign painter. Van Nuys News, 12/18/1950, p. 23

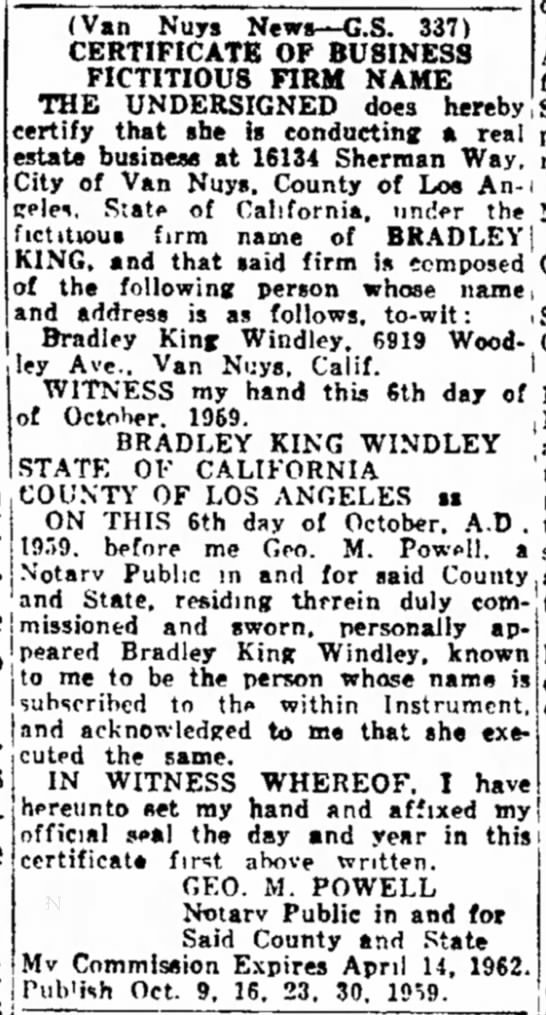

In the 1950 California voter registration rolls, Josephine is listed as Mrs. Bradley King Windley, along with her husband Albert C. Windley. In 1959, Josephine was running a real estate business in Van Nuys, California using the name Bradley King Windley.

Albert Crisp Windley, Josephine’s last husband, died on December 24, 1969. Josephine died August 24, 1977 in Century City, Los Angeles County, California. Information on Josephine’s death comes from www.ancestry.com, posted by a descendant of Madeline’s step-son, James Gaffney Ouellet. She cites both the Social Security Death Index and the California Death Index, which agree that “Bradley Windley” died on august 24, 1977.

A photo of Josephine McLaughlin (Bradley King Windley), followed by a photo of Marjorie O'Connell. They looked remarkably alike.

Images of Josephine McLaughlin/Bradley King from the IMDB website, and from www.ancestry.com

We turn now to the third of the Remarkable McLaughlin Sisters, Madeline.

Madeline Claire McLaughlin (Lilian’s youngest sister). Madeline Claire McLaughlin was the youngest of the three sisters. She was born on June 30, 1897. In her lifetime, she would go by Madge or Mimi, with the surname of her various husbands over the years: Hamilton, Wells, Davis, Ouellet, and Williams.

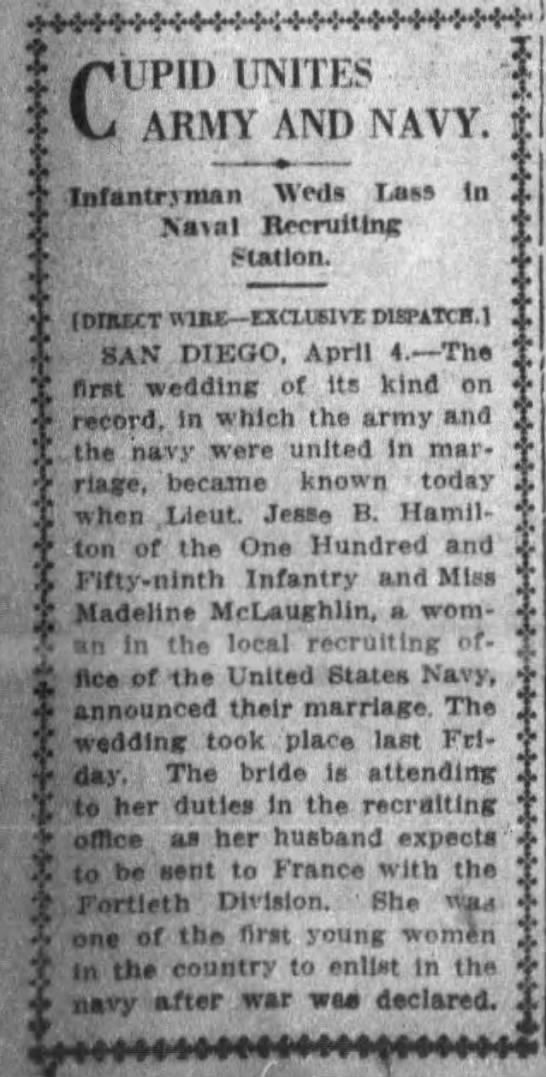

After her time at the Albany Academy of the Sacred Heart, Madeline made her way, by age 20, to the West Coast, perhaps following in Josephine footsteps. In the 1917 City Directory for San Diego, Madeline C. McLaughlin is listed as a 1st class yeoman, USN. She is described in newspaper articles as being one of the first women to join the US Navy after the declaration of war at the beginning of World War I. She was working at the San Diego recruiting office when she got married to her first husband Jesse B. Hamilton, who was in the army. He was expecting to be sent to France. It isn’t clear what happened to Jesse, but he seems to have died by 1922.

Oakland Tribune, 4/4/1918, p. 9

Madeline Claire McLaughlin (Lilian’s youngest sister). Madeline Claire McLaughlin was the youngest of the three sisters. She was born on June 30, 1897. In her lifetime, she would go by Madge or Mimi, with the surname of her various husbands over the years: Hamilton, Wells, Davis, Ouellet, and Williams.

After her time at the Albany Academy of the Sacred Heart, Madeline made her way, by age 20, to the West Coast, perhaps following in Josephine footsteps. In the 1917 City Directory for San Diego, Madeline C. McLaughlin is listed as a 1st class yeoman, USN. She is described in newspaper articles as being one of the first women to join the US Navy after the declaration of war at the beginning of World War I. She was working at the San Diego recruiting office when she got married to her first husband Jesse B. Hamilton, who was in the army. He was expecting to be sent to France. It isn’t clear what happened to Jesse, but he seems to have died by 1922.

Oakland Tribune, 4/4/1918, p. 9

Los Angeles Times, 4/5/1918, p. 8

Madeline’s second marriage was to Roscoe Ward Wells on March 11, 1922. Roscoe was born in Nebraska and moved to Montana as a young child. In the 1910 census, age 20, he was single and living at home with his parents in Montana. His World War I registration card notes that he was working as an entomologist for the State Board in Bozeman, Montana, was single, and had “defective hearing.” Later, he worked for the US Department of Agriculture. They were married on March 11, 1922, in Manhattan, and both are listed in the New York marriage license index for that date. It was Roscoe’s first marriage. On April 3, 1923, Madeline gave birth to a son, Bradley Ward Wells. At the time, the family was living in Middletown, New York, and Roscoe was working as a salesman.

In 1927, they had moved to Newton, Massachusetts, where Roscoe was still working as a salesman. Sometime before 1930, Madeline and Roscoe parted ways. In the 1930 census (April 23rd) Roscoe was living as a lodger in a hotel in Illinois, and reported that he was married (to Madeline). At the same time, “Madge” Wells, married, age 34, was living in Los Angeles as a guest/roomer with her widowed sister Josephine (who was going by Bradley King Wray). Bradley Wells isn’t listed anywhere in the 1930 census. In October of 1930, now divorced from Madeline, Roscoe married a woman named Miriam Holmes in Virginia. On December 31, 1935, Roscoe married a woman named Daisy and was living in Ames, Iowa with his mother Eva, his wife Daisy, and his son Bradley (age 12) . He and Daisy had a daughter born in 1937 in Iowa. By 1940, the family was living in Dallas, Texas, where Roscoe was working as an entomologist. Roscoe died in 1962 in Kerrville, Texas, in a car accident while working as a milk truck delivery driver. He was survived by his wife Daisy and son Bradley. Bradley Ward Wells grew up, served in both the US Air Force and the US Navy, had several wives, and four children. He died in 1999 (see photo below).

In 1930, Madeline and her son Bradley Wells traveled on the S.S. Virginia from Balboa (Panama Canal Zone) to Los Angeles, between January 3rd and January 11th. Later that spring, with her sister Josephine, Madeline travelled on the S.S. Matsonia from San Francisco to Honolulu, Hawaii. She is listed as single on the ship’s passenger list.

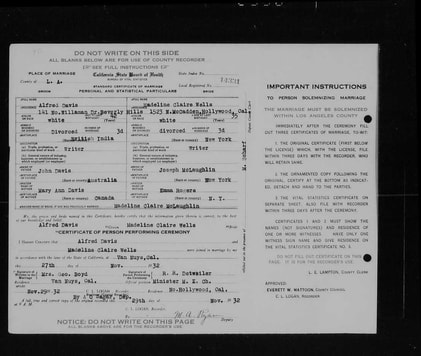

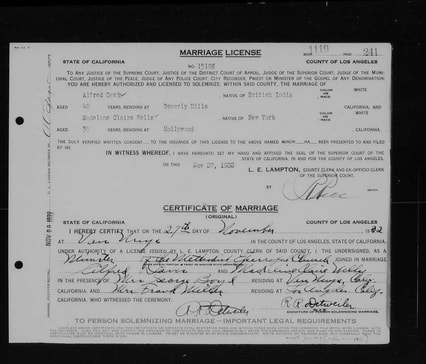

Madeline’s third marriage was to Alfred A. Davis in 1932. They were married in Van Nuys, California on November 29, 1932. At the time of their marriage they are both listed as being divorced, and as being writers. Alfred had been born in British India. Amusingly, the minister who married them was named Detweiler (no relation to this researcher’s husband). The witness at the wedding was “Mrs. George Boyd” (Josephine McLaughlin). They were divorced sometime prior to 1936. In the 1940 census Alfred, divorced, was living in Ramona, San Diego County, California, as a rancher and writer. He is listed on the California voter rolls until 1962.

In 1927, they had moved to Newton, Massachusetts, where Roscoe was still working as a salesman. Sometime before 1930, Madeline and Roscoe parted ways. In the 1930 census (April 23rd) Roscoe was living as a lodger in a hotel in Illinois, and reported that he was married (to Madeline). At the same time, “Madge” Wells, married, age 34, was living in Los Angeles as a guest/roomer with her widowed sister Josephine (who was going by Bradley King Wray). Bradley Wells isn’t listed anywhere in the 1930 census. In October of 1930, now divorced from Madeline, Roscoe married a woman named Miriam Holmes in Virginia. On December 31, 1935, Roscoe married a woman named Daisy and was living in Ames, Iowa with his mother Eva, his wife Daisy, and his son Bradley (age 12) . He and Daisy had a daughter born in 1937 in Iowa. By 1940, the family was living in Dallas, Texas, where Roscoe was working as an entomologist. Roscoe died in 1962 in Kerrville, Texas, in a car accident while working as a milk truck delivery driver. He was survived by his wife Daisy and son Bradley. Bradley Ward Wells grew up, served in both the US Air Force and the US Navy, had several wives, and four children. He died in 1999 (see photo below).

In 1930, Madeline and her son Bradley Wells traveled on the S.S. Virginia from Balboa (Panama Canal Zone) to Los Angeles, between January 3rd and January 11th. Later that spring, with her sister Josephine, Madeline travelled on the S.S. Matsonia from San Francisco to Honolulu, Hawaii. She is listed as single on the ship’s passenger list.

Madeline’s third marriage was to Alfred A. Davis in 1932. They were married in Van Nuys, California on November 29, 1932. At the time of their marriage they are both listed as being divorced, and as being writers. Alfred had been born in British India. Amusingly, the minister who married them was named Detweiler (no relation to this researcher’s husband). The witness at the wedding was “Mrs. George Boyd” (Josephine McLaughlin). They were divorced sometime prior to 1936. In the 1940 census Alfred, divorced, was living in Ramona, San Diego County, California, as a rancher and writer. He is listed on the California voter rolls until 1962.

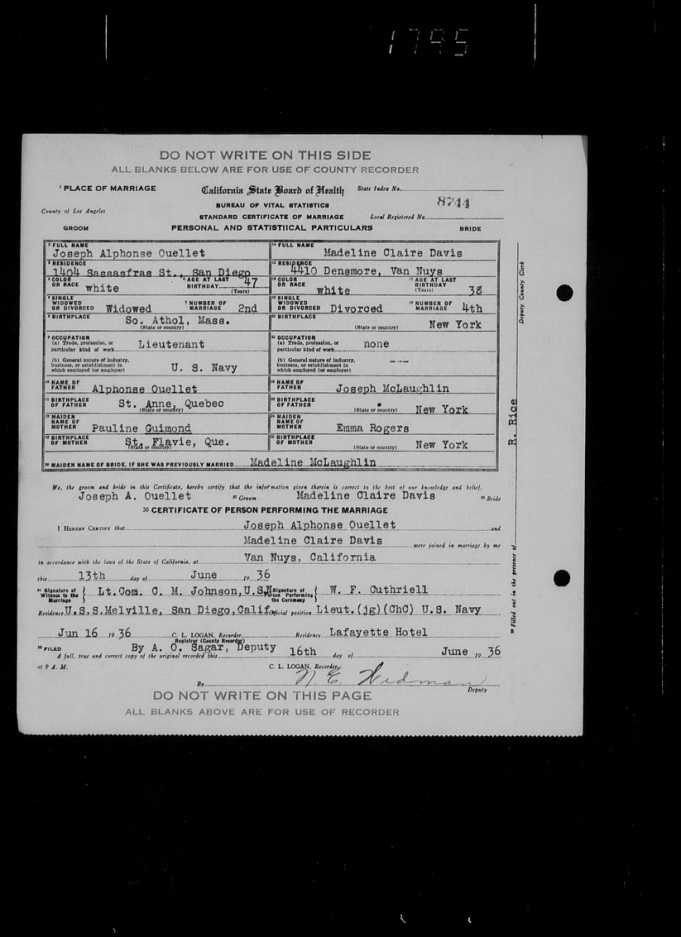

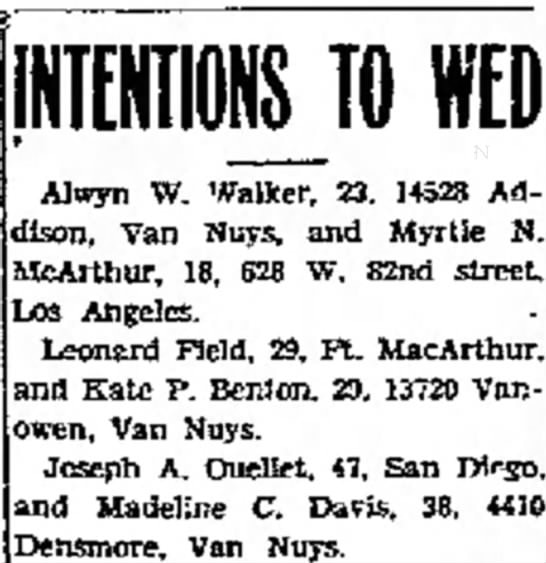

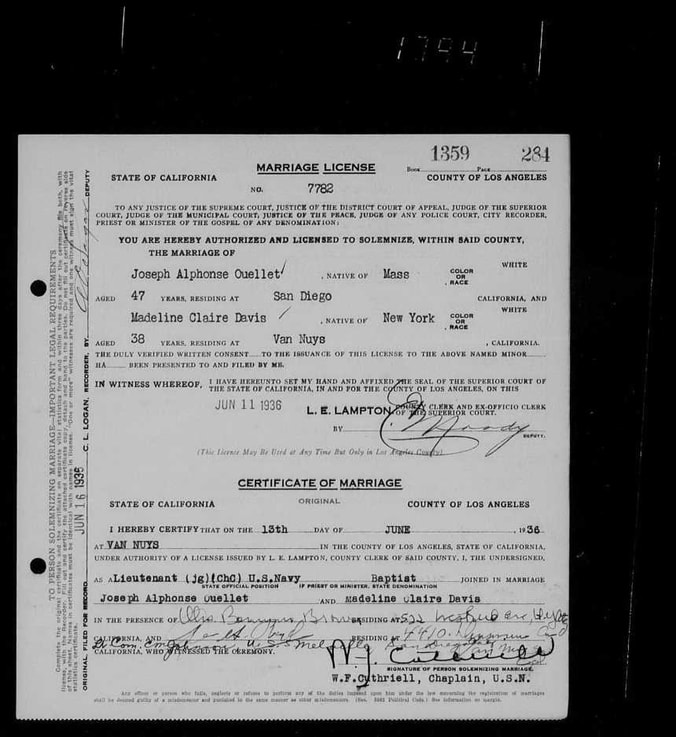

Madeline’s fourth marriage was to Joseph Alphonse Ouellet in 1936. The Van Nuys News, 5/25/1936, p. 1

They were married on June 13, 1936. Joseph had a son, James, from a former marriage. In 1937, Madeline and Joseph were living in San Diego. In 1940, they were stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii, where Joseph was a Lt. Commander in the US Navy. He retired as a Commander.

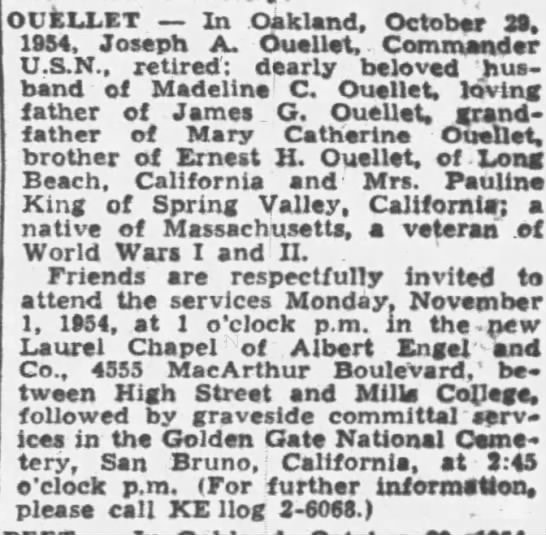

Madeline and Joseph remained married until his death in 1954. Oakland Tribune, 10/30/1954

Mimi Ouellet and her son Bradley Ward Wells, from www.ancestry.com

Madeline’s fifth marriage was to Walter Eldred Williams in 1967. They married in August of 1967 and lived in Sarasota, Florida. Madeline died in 1984, and Walter in 1991.

When viewed in total, these three sisters’ lives seem like something out of a barely-believable novel. From seeming unremarkable childhood experiences, they grew up to be adventurous, ambitious, accomplished women. Both Lilian and Josephine were successful writers. All three of them travelled, especially Lilian. They married often and divorced one or more times; they all outlived at least one husband. Though history has mostly forgotten them, theirs were lives well-lived.

References Cited

Brown, Frances Raymond 1987 Let’s Call Him Barnum. New York: Vantage Press.

Brown, Lilian 1936 “On Safari in America,” Natural History, 37:139-148.

Brown, Lilian 1950 I Married A Dinosaur. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co.

Brown, Lilian 1951 Cleopatra Slept Here. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co.

Brown, Lilian 1956 Bring ‘Em Back Petrified. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co.

Dingus, Lowell and Mark A. Norell 2010 Barnum Brown: The Man Who Discovered Tyrannosaurus Rex. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Keffer, Frank M. 1934 History of San Fernando Valley. Glendale, CA: Stillman Print. Co., pp. 245-246. Online through the auspices of www.ancestry.com.